Introduction

This article describes the compositional and performance practices involved in my 2018 piece Polytope. This microtonal multimedia piece is performed by 4 musicians playing Launchpad Pros in total darkness, with live feed video and electronic 4-channel sound. First, I’ll introduce the musicians who premiered Polytope. I had specific players in mind when I composed it, and knowing their capabilities informed what I wrote. The performance setup also had a big influence on the piece, so next I describe how this mode of presentation has developed in my creative practice leading up to Polytope. After that, I’ll describe the process of rehearsing Polytope. Since the piece has no traditional score, it had to be learned orally in rehearsal.

Polytope

Polytope premiered at Automata LA on March 18 of 2018 as part of MicroFest. I had originally met with MicroFest board member Bill Alves in March of 2017 to discuss making Polytope part of the following year’s MicroFest concert season. That meeting was part of a longer trajectory, continued from a recent residency at the Banff Centre in January of 2017. While in Banff, I had started to work on Polytope with 4 Launchpad Pros that Novation had leant me. While there, I made several short video demos that I used to book performances of Polytope.

Around the same time that I met with Bill, I also met individually with a few musician friends that I wanted to play Polytope with me: Andrew Lessman, Cory Beers, and Erin Barnes. Over tacos and/or beer, they each said that they’d love to be part of the group. In order to play Polytope, musicians need specific skill sets – some of which are outside of typical classical training. When forming my Polytope group, some traits I considered important were:

| Experience performing musical minimalism | Standard pieces by composers like Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Terry Riley, etc. |

| Good rhythm | Not only an ability to lock into a rhythmic pulse and play in odd time signatures, but also an attentiveness to space and process. |

| Good with new musical interfaces | Besides the fact that the Launchpads are drastically different from a piano keyboard, the software setup is idiosyncratic enough that it’s not feasible for most players to bring the Launchpads home to practice. Thus, they need to be able to learn the piece in rehearsal only. |

| Ability to learn the piece orally | Not only is Polytope difficult to practice, it has to be memorized and there is no score in standard notation. |

Considering these traits led me to the following group

- Erin Barnes is the diamond marimba player in the LA-based Partch ensemble. She’s also a hiking friend

- Cory Beers is mostly known as a cimbalom player, but is also a fantastic percussionist.

- Andrew Lessman is a jazz and rock drumset player whom I’ve worked with for years.

These musicians have played in all performances of Polytope except one. For a performance on March 1, 2020, drummer Trevor Anderies and composer Federico Llach subbed for Erin Barnes and Cory Beers. Since neither Trevor nor Federico had played Polytope before, I had multiple one-on-one rehearsals with both before we met as a full group with Andrew.

Initial Rehearsals

In July of 2017, we had 2 initial rehearsals, during which I introduced the sections of Polytope that I had finished thus far. I showed everyone their respective parts, made sure they understood them, and then we tried to play them slowly. We came across some unexpected physical limitations that needed to be addressed. Erin, Cory, and Andrew were all percussionists, and they were used to using between two and four sticks or mallets. This made them very adept at using up to two fingers per hand, but less comfortable with more than that. In addition, some sections of Polytope had to be slowed down.I had reused some material from an earlier solo piece, and it wouldn’t be feasible to ask others to learn it at the original tempo.

I hadn’t yet decided on whether we would stand or sit when performing. I stood for all of my solo Launchpad pieces, with the Launchpad Pro sitting on a PVC mount that itself rested on an X-shaped keyboard stand. After confirming that the rest of the group also preferred to stand, I made a similar setup for Polytope.

Setup

Launchpads

This might be a good time to talk about the Launchpad-based setup. For those who don’t know, a Launchpad is a MIDI controller featuring an 8×8 grid of square buttons, which is most commonly used in conjunction with Ableton Live. I began working with Novation Launchpads in 2014 because the Launchpad Mini was cheap. I wanted to make a demo of a microtonal sound installation patterned after a Plinko game, but with the wooden dowels replaced by piano wire tuned to a JI tonality diamond.

To visualize the Plinko game, I turned the Launchpad 45° to emulate a tonality diamond. James Tenney had encouraged me to read Partch’s Genesis of a Music in 2005, though I didn’t get to it until 2008. That year, I had a regular 45-minute train ride from Highland Park to Hollywood to teach after-school art, and the consistent rhythm of that commute gave me plenty of time to read. However, it took me until 2015 to complete a piece that incorporated Partch’s ideas and that I was happy with.

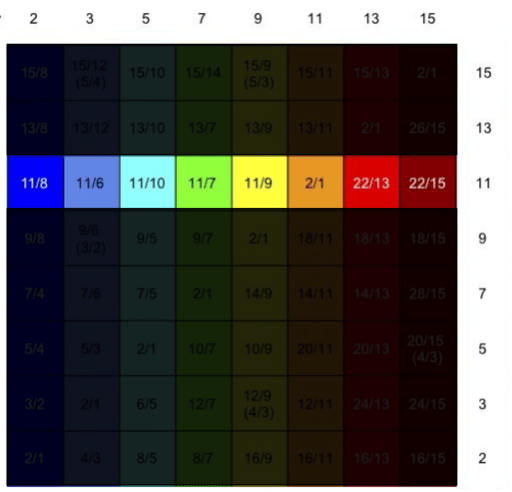

I made the following score for the microtonal Plinko installation. To imagine the layout of the installation, one should turn the score 90° clockwise. Each ratio represents the physical position of a string and its interval relationship to the 1/1 (432 Hz) at the vertical center of the score. At the left side of the score (which is the highest vertical point of the Plinko installation), the ratios are small whole number integers in a 3-limit tonality diamond. As the puck descends the face of the installation, it travels through ten tonality diamonds with limits of 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 11, 9, 7, 5, and 3. This increasing and decreasing complexity creates an A-B-A arch form, within which the Plinko puck stochastically plays whichever pitches gravity dictates.

I conceived of this installation while in residence at the Marin Headlands Center for the Arts, where I had an expansive studio space. After the residency, it was painfully clear that I had no room for large physical art objects. However, I realized that I could perform the Plinko score on the Launchpad Mini, and that performance became Diamond Pulses.

This is also when I added live-feed video, but I’ll discuss that later. I designed Diamond Pulses to be portable for touring. Without a PA or projector, the setup fits in a carry-on suitcase with my clothes and other items.

After a Novation rep saw me perform Diamond Pulses on dublab internet radio, Novation lent me a Launchpad Pro to develop my 2nd Launchpad piece, titled Comma.

The Launchpad Mini has push-buttons, but the Launchpad Pro has velocity-sensitive pads, bringing it a little closer to a playable musical instrument. While the notes in Diamond Pulses change as the piece progresses through multiple tonality diamonds, Comma instead uses only 14 different pitch classes in a single tuning system of stacked just 5ths (+2¢ each). This change was clearly influenced by the shape of the Launchpad Pro, while Diamond Pulses used the Launchpad Mini to demo a pre-existing idea.

When Novation saw Comma, they leant me 3 more Launchpad Pros to develop Polytope during my 2017 residency at the Banff Center for Arts and Creativity.

Tuning Polytope

I originally planned to spend my time at Banff designing a series of multi-dimensional pitch lattices for Polytope.

However, as I explored several options, the constant structures sounded too clinical and clean.

However, when I programmed the Launchpads to play a 15-limit tonality diamond, I found the intervals to be much more surprising and to my liking. To vary the frequencies, I brought the top launchpad and the Right Launchpad up one octave, and lowered the Right and Left Launchpads by 12¢ to give them a slight “shimmer” – akin to the violin stop on an accordion.

Sound

To perform Polytope, I run Pure Data and Ableton Live simultaneously. Ableton controls the sound, while Pure Data controls the lights of the Launchpads and some MIDI routing to Ableton. While my past Launchpad pieces were made in Mainstage (a performance-oriented offshoot of Logic), Ableton’s session view proved to be the most efficient to write this loop-based music on 4 simultaneous instruments.

While Ableton is more functional than Mainstage, this causes it to have slightly more latency. Because of this latency, we discovered that the best way to stay in rhythmic sync is to listen to the sounds of our fingers tapping the pads of the Launchpads, rather than the sounds coming from the speakers. This highly-localized sound is quiet enough to be hidden from the audience, who instead hear the electronic sounds through the speakers.

I programmed all of the pitches in Ableton’s Sampler, starting from a recording of a sine wave. Each player’s instrument can switch between 2 possible dynamic envelopes: one with a very short attack and medium release (referred to as a pulse), and the other with both a long attack and a long decay (referred to as a swell). Originally, I changed each player’s envelope manually with 4 buttons on a SoftStep foot controller. This was useful in composing, but for performance I streamlined this process in Pure Data, so that a single button on the SoftStep would sequence through the sections of Polytope.

Visuals

In my performance setup, an overhead camera is pointed straight down at the Launchpads, picking up the lights of the launchpads and the silhouettes of the players’ fingers. A goal for all my Launchpad pieces is to explore different spatial metaphors for music, and with Polytope, this reorientation began immediately. Due to the placement of the Launchpads’ USB port, they all had to be turned 315° to fit together snugly.

When arranged properly and viewed from above, the notes at the center of the quartet are highest in pitch while those at the outer perimeter are lowest. In addition, the pitches on each Launchpad go from low to high as you play from Right to Left.

My decision to make live feed video part of these performances was partially inspired by my repeated disappointment in the performance presentation of high-calibre laptop music. While I love the music, I often find something lacking in the presence of the live performers – often just a seated musician doing SOMETHING on their Apple laptop.

Having spent many years working with theater and experimental puppetry, my approach drew influence from artist László Moholy-Nagy’s idea of a “Theater of Totality.” In this approach, all of the elements that make up a performance are given equal footing – rather than being subservient to a text, composition, or human actor.

…the Theater of Totality with its multifarious complexities of light, space, plane, form, motion, sound, man – and with all the possibilities for varying and combining these elements – must be an ORGANISM (Gestaltung). Thus the process of integrating man into creative stage production must be unhampered by moralistic tendentiousness or by problems of science or the INDIVIDUAL… all other means of stage production must be given positions of effectiveness equal to man’s…

Moholy-Nagy, László.“Theater, Circus, Variety.” The Theater of the Bauhaus, by Oskar Schlemmer et al., Wesleyan University Press, 1961, pp. 49–70.

Moholy-Nagy saw that the full message of a theatrical performance was larger than just the actors on stage. It included all of the media that enabled the experience, from the lights hanging in the grid to the wood of the stage floor. In Polytope, the musicians are onstage but their direct physical presence isn’t the main visual focus. Rather, attention is directed to the enlarged projection of the players fingers over the Launchpads – an abstracted interplay of digitization and corporeality. The music and visuals are both integral, unlike most music performances where the visuals are subservient to the music. My performance setup also draw influence from Wayang Kulit shadow puppetry, Light and Space Art, Bridget Riley’s Op art, and Visual Music by the likes of Oskar Fischinger or Mary Ellen Bute.

Rehearsing Polytope

In the 2 months leading up to the premiere of Polytope in March of 2018, we had 8 weekly rehearsals. The other 3 musicians came to my house each week and rehearsed for about two hours. I’d usually have some simple food cooked, like rice and vegetables. We would eat and talk for a bit, then rehearse, and eventually everyone would head home.

The lights of the Launchpads are the score that the players follow, but they needed to know how to interpret the score. Since it’s difficult to represent in standard notation, I decided to teach all of Polytope orally. Depending on the section, I would either show everyone their respective parts on their Launchpad, or show them the identical process that I would be playing on my Launchpad.

During each of the first 4 rehearsals, we worked on ¼ of Polytope. In the remaining 4 rehearsals, we worked on problematic sections and practiced running the full piece. Though it’s an hour of music to memorize, ultimately Polytope consists of only 15 formal processes and the transitions between them. When learning Polytope, we focused on those 15 processes first, and then learned the transitions.

The following diagram shows the 15 sections of Polytope, with the name of each section in the second column (I’ll refer to this diagram several times in the coming sections). The terms used in this diagram are explained in more detail later. The third “type” column shows which of the three types each section is: Swells, Pulses, or Shape. The fourth “Rules” column gives a very basic description of how each section progresses and is interpreted by the players. The fifth “Envelope” column shows which of the two dynamic envelopes are used in each section. The sixth “Rhythmic relationship” gives one of several ways the players’ parts relate to each other: Parallel process, Hocket, or Individual Parts. In addition, some sections play in rhythmic “complement.”

Rehearsal 1

In the first rehearsal, we focused on the first 4 sections of Polytope. I decided not to set up the projector until the fifth rehearsal. So, these first 4 rehearsals were not done in total darkness, but in dim light. When rehearsals took place during the day, I closed the blinds or put blankets over the windows.

Red Swells

Polytope opens with Red Swells. In all of the sections with “Swell” in the title (see “Polytope Form” Diagram above), the notes have a “swell” envelope with a long attack and long decay.All of the Swell sections – except for Purple Swells – correspond to a Utonality, while all of the “Pulses” correspond with an Otonality (these are Harry Partch’s terms for tuning ratios that have a common denominator and numerator, respectively). My treatment of the rows and columns of a tonality diamond as formal elements was inspired by Arnold Dreyblatt’s “Orchestra of Excited Strings.”

“These mathematically related overtones are heard as tonal relationships when they are transposed and sounded above a fundamental tone. It is as if one changes key, but retains the root fundamental at the same time… I would conceive the structure in terms of “blocks” or “loops” which are comprised of a rhythmic pattern, a tonal chord, and a specific instrumentation including any specific performance techniques.”

Dreyblatt, Arnold. “Origin and Development of the ‘Excited Strings.’” Arcana IV: Musicians on Music, edited by John Zorn, Hips Road, 2009, pp. 71–89.

Dreyblatt refers to it as a “Magic Square” rather than a tonality diamond, but the function is the same. In Polytope, a Utonality or Otonality corresponding to each of the odd numbers from the 15-limit tonality diamond is featured in one section (meaning a single row or column from the tuning system shown above). Red Swells corresponds to the Utonality of 15.

In Red Swells, the players start at their highest-pitched note and play all of the visible notes in contiguous, descending order. Each note should be the length of a deep breath or a long bow on a violin, followed by a pause of indeterminate length before playing the next note. I refer to this as playing in rhythmic “Complement.”

In sections with “Complementary” rhythmic relations (see “Polytope Form” above), the musicians play when they expect other players to not be playing. I’ve used this sort of “anti-ensemble” playing in many other pieces, and it requires a great deal of sensitivity to the internal rhythms of the other performers. Parts will inevitably overlap, but they should never be played in rhythmic unison.

All of the “Swells” or “Pulses,” sections progress by the visible line shrinking or growing. I use a foot controller to progress through the piece, and this progression is mostly based on my own internal rhythm. However, I also try to be sensitive to what the other players are doing. In Red Swells, I try to wait until all of the players are playing notes that will not disappear in the next “scene.

Each section of Polytope has clear rules that are simple to follow once they are learned. The transitions between sections are trickier. Whenever the transitions are staggered, my part is usually first to change. This way, the other players are reminded of what section comes next. This is true for the transition to Square.

Square

Square changes the envelope from a swell to a pulse – with a short attack and medium release. In Square, all of the players do the same parallel process on the same rhythmic pulse. However, their individual downbeats will vary – similar to Terry Riley’s In C. In Square, the musicians play every visible horizontal row on their Launchpad, from right to left, and from low to high. When a row appears or disappears, players adjust their rhythmic cycle accordingly. If they are playing a row and it disappears, they finish that row and then move on.

While the Swells and Pulses relate directly to the underlying tonality diamonds, the “Shape” sections do not. Instead, more complex harmonies arise.

Square ends with each player playing a horizontal white line of 8 notes. In the following transition to Red Pulses, there is as light ritardando in preparation for the later Circles section. The white line disappears, one note at a time, as the red line grows. And, eventually the red line takes over.

Red Pulses

The notes in Red Pulses correspond to an Otonality of 13.

In this section, the players choose any 2 visible notes and repeat their chosen notes on a shared pulse. They start at pianissimo, crescendo to forte, and then decrescendo again. These gestures are played in the same sort of rhythmic “Complement” as the Swells sections, and with approximately the same durations of gestures and rests. Players only change notes between gestures. I trigger each player’s transition to Red Pulses when my own gesture is at its loudest, so that players are less likely to play in parallel.

Circles

A unison transition brings the players to section 1 of Circles. The Pure Data programming for Circles was taken straight from my earlier solo piece Comma.

In the Circles section of Polytope, the musicians play identical material in a counterclockwise hocket. There are 3 parts to Circles. The first part has a single 4-note cycle. The second part adds a 12 beat cycle, and the third adds a 20-beat cycle. Transitions within Circles always occur when the red, orange, and yellow diamonds align vertically from the players’ perspectives. Sections 1 and 2 repeat until I cue the transition. Leading up to the transitions, I whisper “1-2-3-4…” and then press the foot pedal to cue the next section. The full rhythmic cycle of section 3 is played only once. In this part, the red diamond’s 20 beat cycle repeats 3 times, the orange diamond’s 12 beat cycle repeats 5 times, and the yellow diamond’s 4 note cycle repeats 15 times. When this cycle completes, there is a unison transition to the “coda” of Circles.

While Circles is conceptually simple, it is quite challenging to play. Before every performance, the group always runs Circles slowly as a warm-up.

Learning these 4 sections was enough material for one rehearsal, so we called it a day and everyone went home.

Rehearsal 2

Orange Swells

When we met the following week, we started by reviewing the previous week’s material. Then, we moved on to Orange Swells, which has a Utonality of 11.

I transition to Orange Swells first, and the other players see the process in my part. Players choose any 3 visible notes, and play them in rhythmic Complement. As the section progresses, the notes disappear from the middle of each player’s line.

Arrows

Player 3 transitions to Arrows first, and dictates the tempo. This tempo can’t be too fast, because player 4 has a very difficult part at the end of Arrows. The meter in this section alternates between ¾ and 6/8. Everyone starts in unison, but players 2 and 4 soon start playing more intricate polyrhythms.

This section requires a lot of rehearsal, especially for player 4 who has to play an unchanging group of 3 in one hand while the other hand alternates between ¾ and 6/8. This particular rhythm came from another earlier Launchpad piece called One Line, which pianist Vicki Ray played at Pianospheres in April of 2018.

This was the first time one of my Launchpad pieces was played entirely by someone else. I was using the Launchpad Pros to perform Polytope, so I couldn’t lend one to her. So, instead, I wrote out the part as piano music and she learned it that way first.

Orange Pulses

In the transition from Arrows to Orange Pulses, my part changes first. Orange Pulses corresponds to the Otonality of 9.

In this section, players choose any 3 notes and play upward arpeggios in time with Arrows. Player 4 is the last one to transition. I follow their part, and, when their rhythmic cycle is coming to an end, I give them an audible breath and head nod to guide their transition to Orange Pulses.

Purple Swells

The lines in Orange Pulses shrink from both ends, and eventually Player 2 is the first to transition to Purple Swells. Unlike other Swell sections, there is no Utonality underneath Purple Swells. Instead, every time a player releases a note, Pure Data chooses a new random note for them to play next. This is the easiest section to play, and is a chance to take a mental breather.

By the time we reach this section in performance, my right foot has often fallen asleep. In order to keep my left foot hovering above the Softstep pedal, I stand in practically the same position throughout the piece. Since there are no scene changes in Purple Swells, I can shift my posture and shake out my legs.

Rehearsal 3

Yellow Pulses

The following week, we again started by reviewing what we had done in the last few weeks. Then, we worked on Yellow Pulses which corresponds to a 7 Otonality.

In Yellow Pulses, all of the players choose any 4 visible notes and play descending 4-note arpeggios. Unlike the other Pulses sections, the players should never have a shared pulse, and they’re allowed to speed up or slow down at will. As this yellow line becomes uneven, the players follow it, continuing the same process as before.

Square 2

When the visible notes form a horizontal line from the players’ perspectives, I start playing in a set tempo. The other players individually lock into my pulses, and once they do, Square 2 starts. The rules to Square 2 are identical to the first Square, but in reverse. Musicians play every visible note from left to right, and one row at a time in descending order. The end of Square 2 has lots of low-integer JI intervals in a low register, which sounds great when a venue has a sub.

Blue Pulses and Green Swells

As the process of Square 2 ends, Players 1 and 3 transition to Blue Pulses and Green Swells. This is the only section that has both a Utonality and an Otonality.

The Green Swells are played by players 2 and 3 and have a 5 Utonality. The musicians play swells of any 4 visible notes. The Blue Pulses are played by players 1 and 4 and have a 3 Otonality. These players choose any 5 notes and play ascending 5-note arpeggios. During this section I gradually accelerando to the tempo of the next section, Green Line.

Green Line

The Green Line section features the musicians playing in visual “unison,” but only from the audience’s perspective. In order to play the same part as player one on the bottom of the screen, player 3 must play the same part upside down, while players 2 and 4 must play it at plus or minus 90°. Though the size of the shape changes, the meter is consistently 13/8 (3 + 3 + 3 + 4). I only trigger scene changes at the moment when the players first entere the 4-beat square in the center. This gives them a few beats of warning before starting the new pattern. At the end of Green Line, all of the players loop the center 4 notes.

Rehearsal 4

In the 4th week, we again started by reviewing past material. Then, we pick up from the ending 4 notes of Green Line, which go straight into Red Line.

Red Line

In Red Line, players 1 and 3 change their meter before players 2 and 4. Everyone should have a different downbeat, and if 2 the downbeats of 2 players match, one of them should restart their pattern at the beginning. We first practiced this section very slowly, but once everyone figured out a good fingering it was simple to play at tempo. Once all the players’ registers have reached their highest and lowest notes, then there is a ritardando to the tempo of the Coda.

Coda

In Coda, everyone plays octaves. It is surprisingly difficult, because you have to quickly cross the entire Launchpad. Out of necessity, we decided to slow this section down. As in Red Line, Players 1 and 3 change first, followed by players 2 and 4. The vertical lines shrink from the top down, and the changing polyrhythms are more explicit than in Red Line.

White Swells

When there are only a few notes left, I’m the first to transition to White Swells, which has an Otonality of 1.

In this section, the musicians play dyads of contiguous notes. These notes are in 4 groups, and the musicians play these groups in descending order. The line shrinks by 2 notes as the section progresses, until there are only 2 notes left. At this point, players alternate between those 2 notes. When there is only 1 note left, everyone plays swells on that one note until I trigger the last scene, which has no visible notes. Players individually finish their last swell and those notes are allowed to decay in the darkness.

Having spent a month learning all of the sections in Polytope, we spent the remaining 4 rehearsals working on difficult sections and practicing running the whole piece. We also started rehearsing in darkness with the live feed video.

Final Thoughts

sine waves. An album of Polytope was released on Orenda Records in 2018. However, the COVID-19 has thus far thwarted my plans to get good video documentation of it. Though we’ve performed Polytope many times now, I don’t yet have satisfactory documentation of it. There have been great performances of it, and we had planned to record a high-quality video in summer of 2020. But pandemic conditions were not in our favor, so those plans were put aside for the time being. As safety guidelines continue to change, I hope to finally get a great performance video of Polytope.